The Anatomy of the Past 12 Fed Rate Hikes

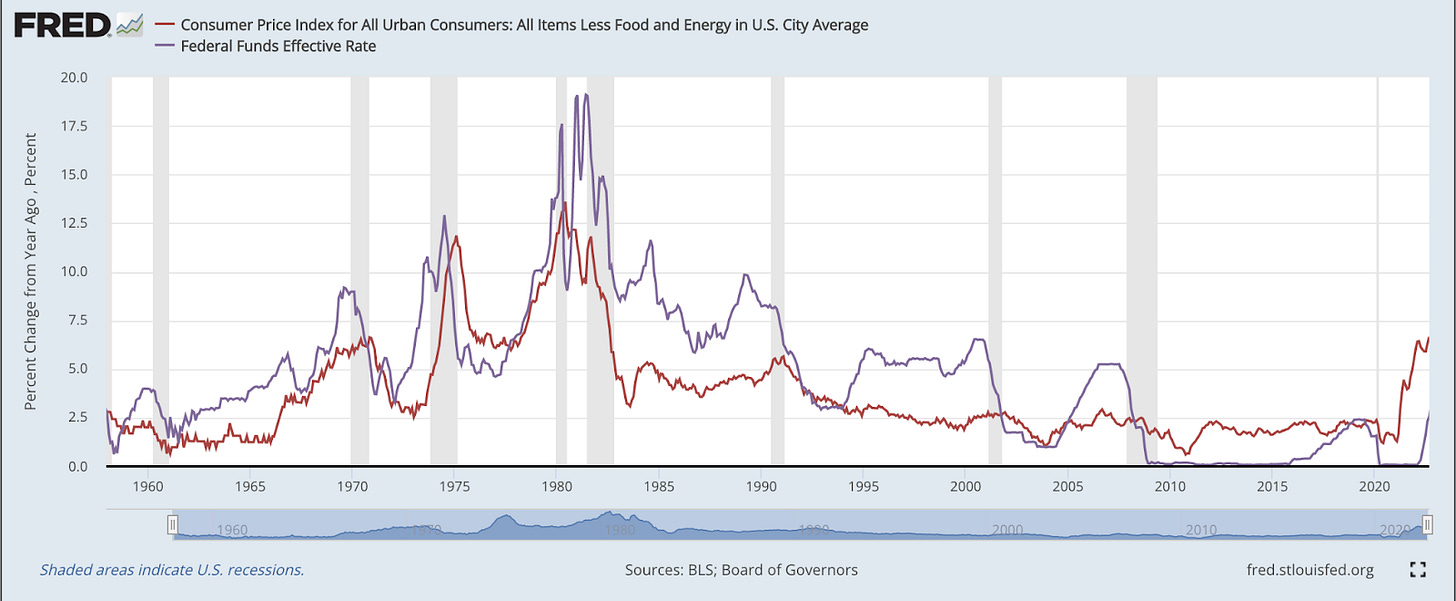

A history of rate hikes and their impact on inflation from the 1960s to 2022

The inflationary environment of today has not existed since the 1970s. So we performed a historical analysis to understand how the Federal Reserve used interest rates to fight inflation. We looked into how aggressively the Fed hiked rates in the past. We compared the impact of different terminal rates to their effects on inflation. And we looked at how quickly inflation responds to various rate hikes.

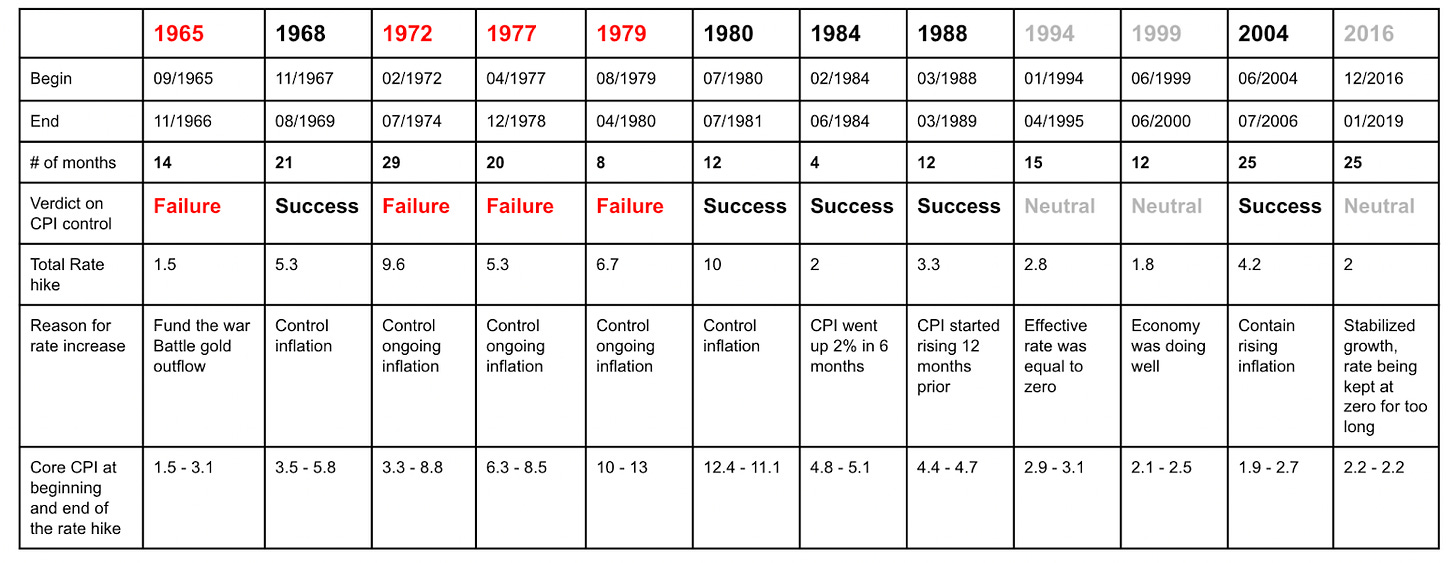

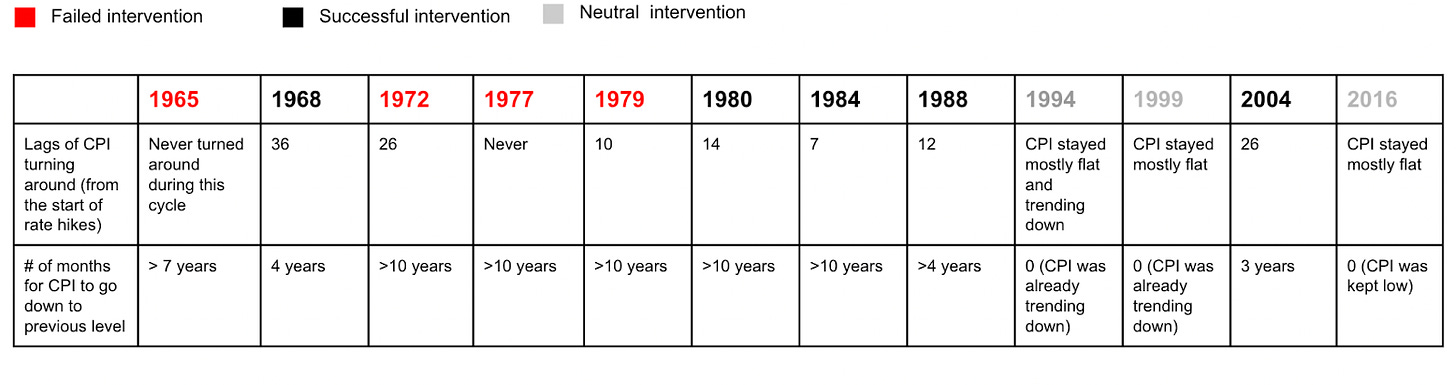

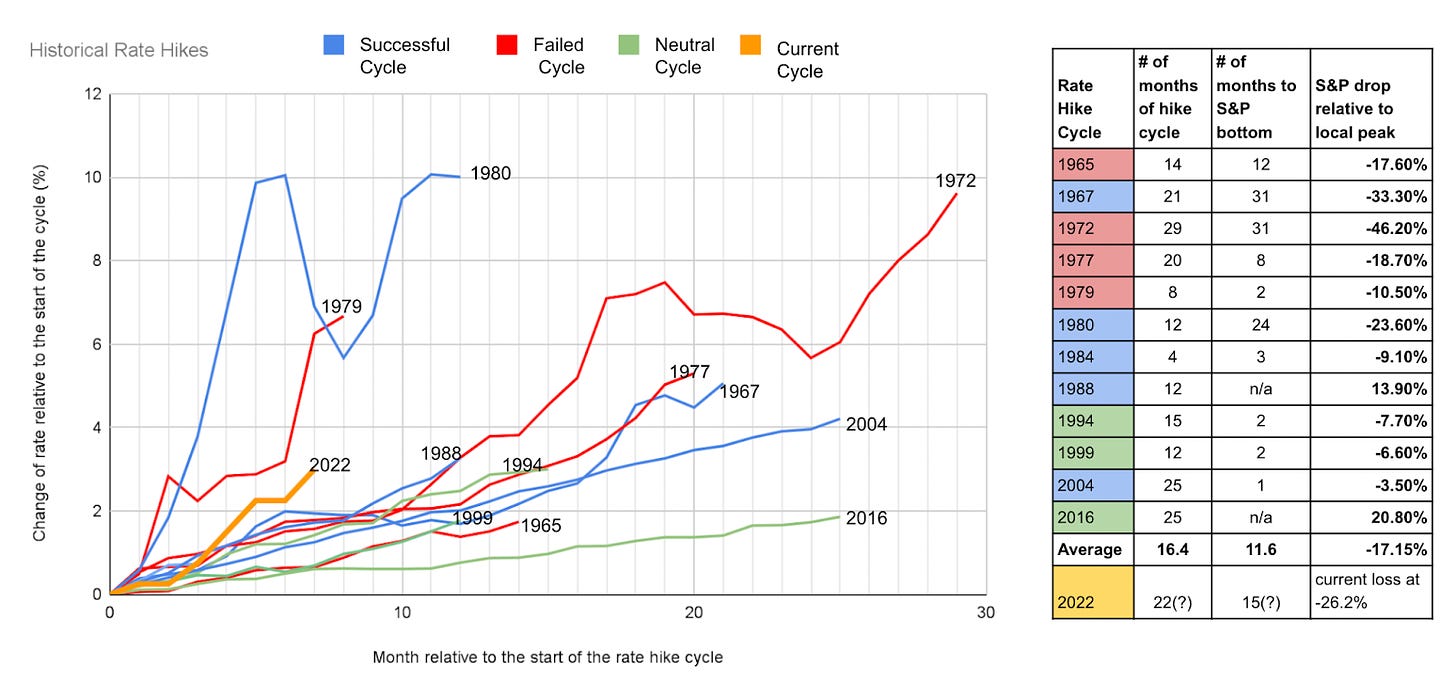

We decided to look at the past 12 rate hikes since 1965, whether they were successful, and what it took to be successful. Even though each rate hike is unique in the circumstance that leads to the rate hike, they serve as a good starting point for a glimpse into the high probability future state of this volatile time. Of the previous 12 rate hikes since 1965, 5 were successful, four failed, and three were neutral. We define the efficacy in terms of their result in bringing inflation down.

All five successful rate hikes brought inflation down to some degree, although it took a long time to return to the equilibrium of 2-3%.

The four failed rate hikes did not bring inflation down at all. On the contrary, core CPI is rising together with rate hikes.

The three neutral rate hikes did not target inflation and had no significant effect on CPI.

This analysis isolates interest rates and does not account for other factors that impact inflation, such as wage growth, global tariffs, or changes in international trade. Moreover, we focus exclusively on Fed Fund Rate for inflationary analysis because Fed Fund Rate has been the primary driver of the macro-economic landscape to fight inflation in the last year and will continue to be the primary driver in the next few years.

Summary

Based on our analysis, the rate hikes in 2022 are aggressive enough to bring down inflation, but the terminal rate is off by 100%. A 5% terminal rate (as projected by the Fed) is insufficient to bring down inflation. Maintaining a 9-12% terminal rate for more than 12 months is needed. Assuming we hike at the current FFR of 50 basis points per month, it will take another 12 months (until December 2023) of 75 basis point hikes to bring us to 10% from our current rate of 4% (November 2022). Our data is at odds with the narrative from the Fed. The Fed projects another 75 basis point hike, then slowly increases to a terminal rate of around 5%. There is significant risk as the markets and the Feds grapple with both the narrative of terminal rates and the actions taken by the Feds to continue raising rates to 9-12% or pause and possibly let inflation become endemic.

Rate Hikes Categorized by Efficacy

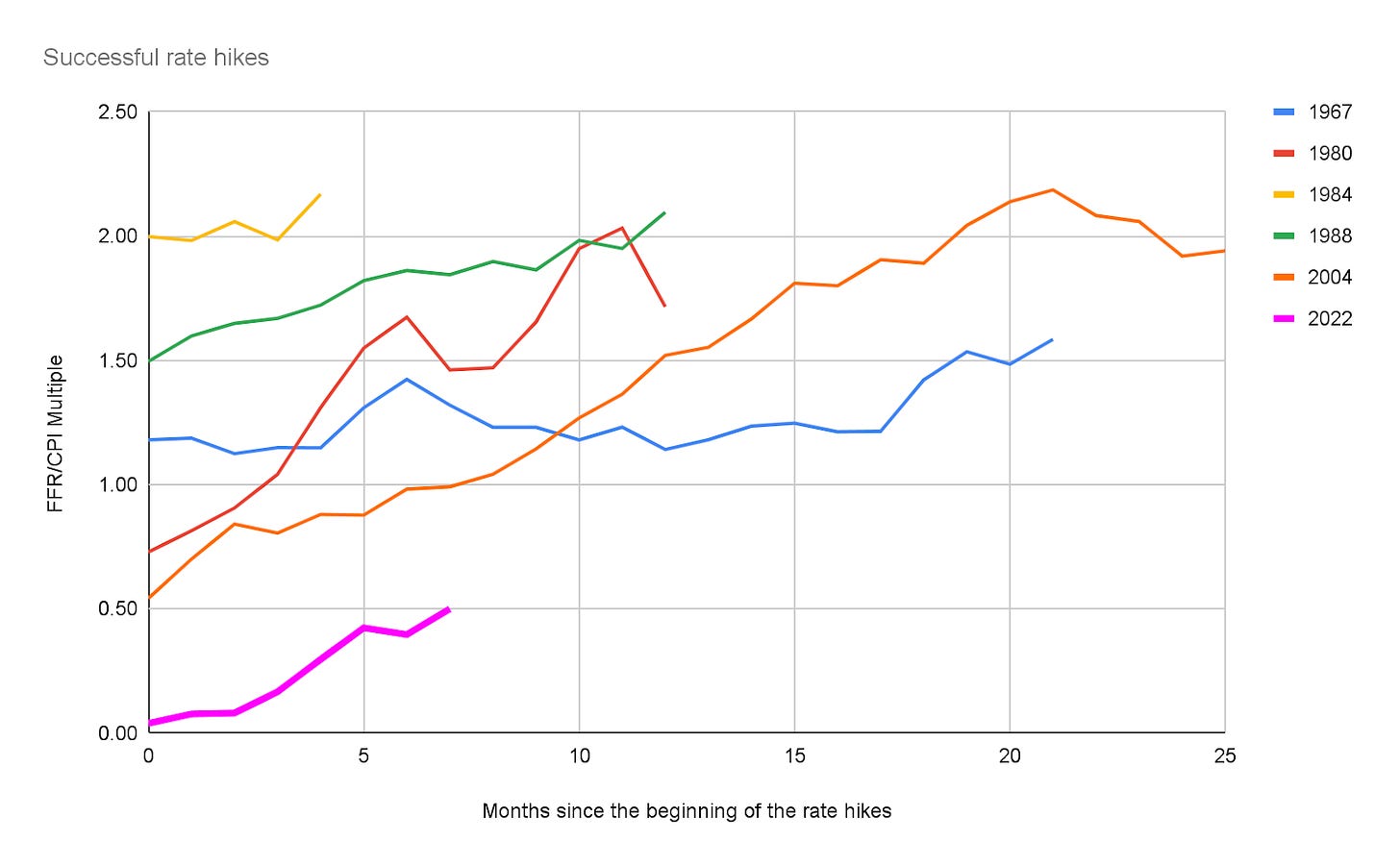

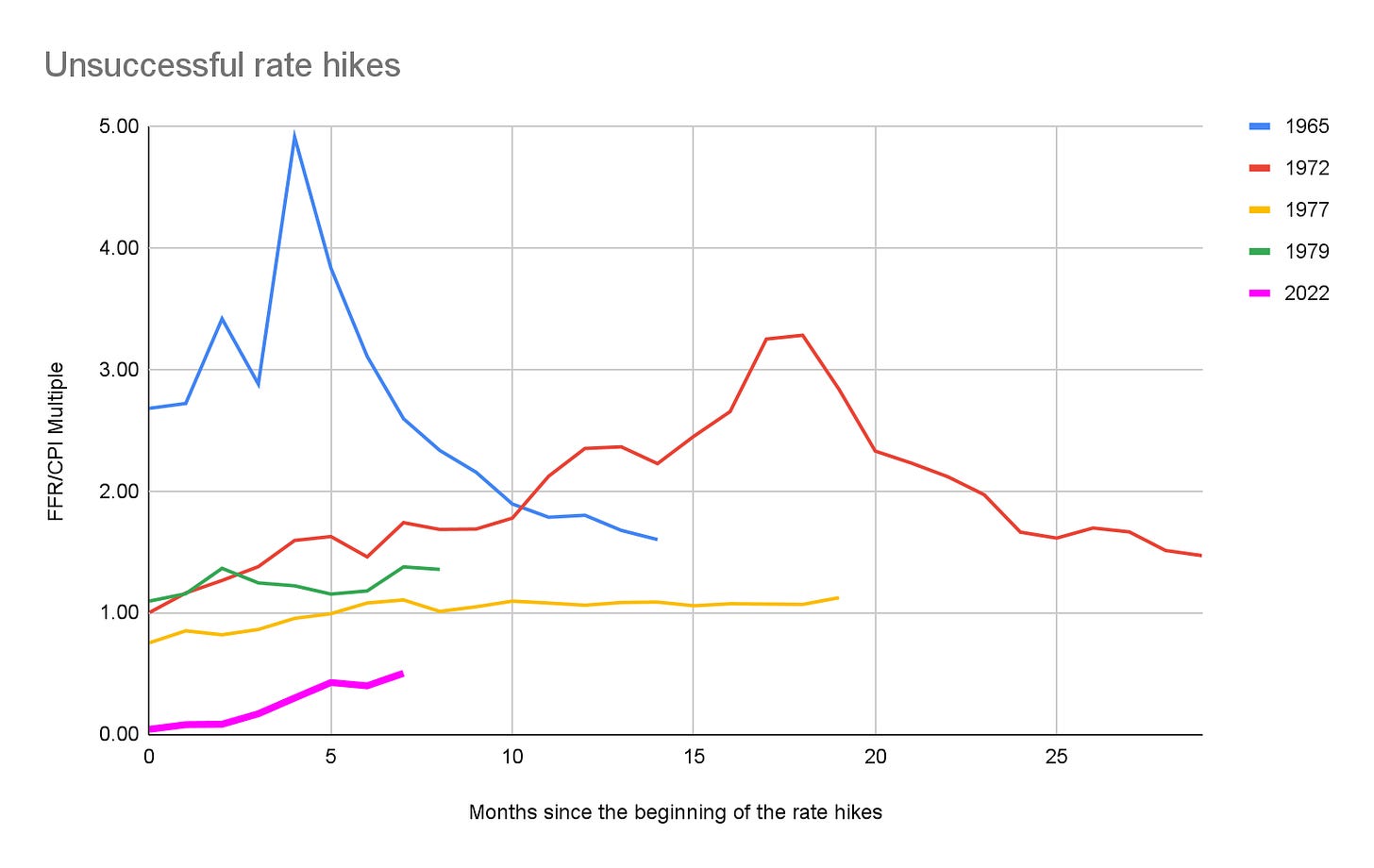

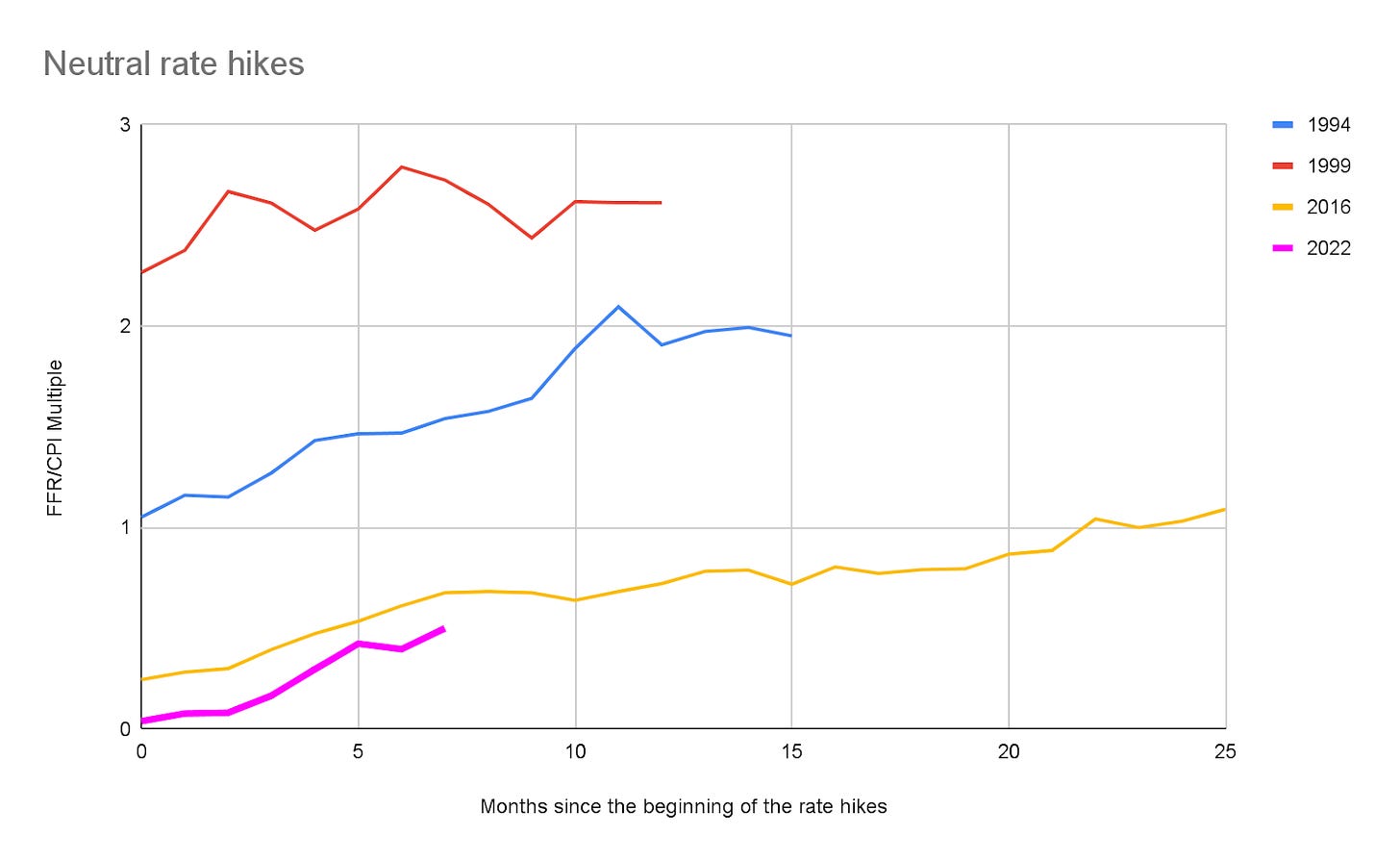

We normalized the rate hikes by finding the multiple of the Fed Fund Rate over Core CPI at any given month of the cycle. Conceptually, this can be understood as rate hikes aggressiveness relative to CPI. Multiple=1 is when Fed Fund Rate equals the Core CPI.

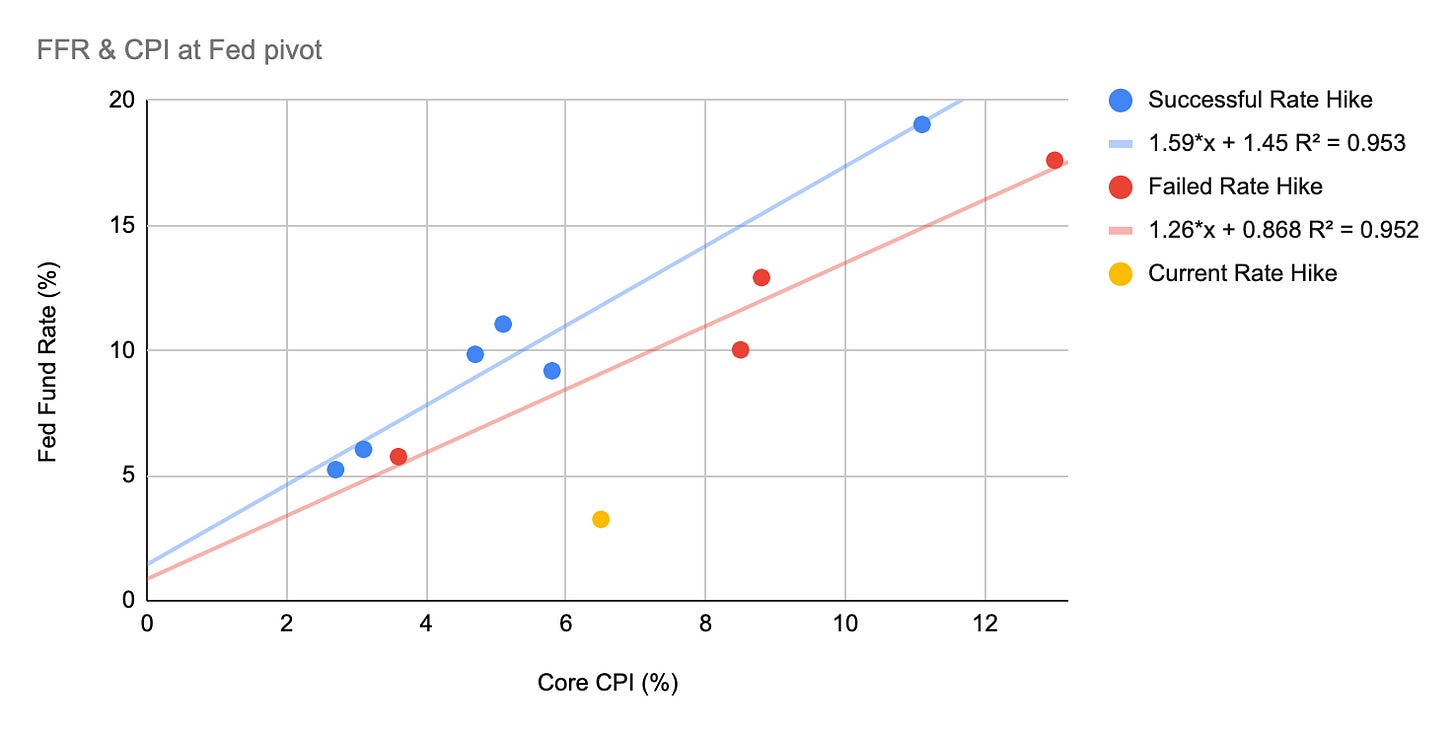

The successful rate hikes are consistent with each other and orderly, with solid and steady raises of FFR/CPI Multiple averaging 0.1 per month. The most famous rate hike in 1980 with Volker saw an increase of multiple of 0.3 per month. The successful rate hikes quickly entered multiple>1 zones, if not already started at >1. FFR/CPI multiple ended at least 1.5 at the end of the rate hike, meaning the terminal Fed Fund Rate was at least 1.5x of Core CPI at the time of the Fed pivot. For all successful rate hikes, Core CPI only started trending down after the Fed pivoted, with an average of 4 months lag.

The rate hikes we see in 2022 so far track well in terms of aggressiveness (an increase of FFR/CPI multiple per month) relative to successful rate hikes. But we might be far below the successful terminal rate.

Unsuccessful rate hikes are disorderly, and we observe significant differences in FFR/CPI multiple from the successful ones. They failed either because the rate hikes needed to be more aggressive to contain inflation (1977, 1979) or too aggressive and had to pivot prematurely (1965, 1972).

Neutral rate hikes are shallow, averaging a 0.05 increase in FFR/CPI Multiple per month, and had no impact on CPI even when carried out over two years (2016).

Inflation is Sticky

Successful rate hikes not only need to be at a high terminal rate relative to CPI, but it also needs to maintain that rate long enough for inflation to come down. We define CPI turning around as core CPI starting to consistently trend downwards (more than 0.3% down from the peak and continuing).

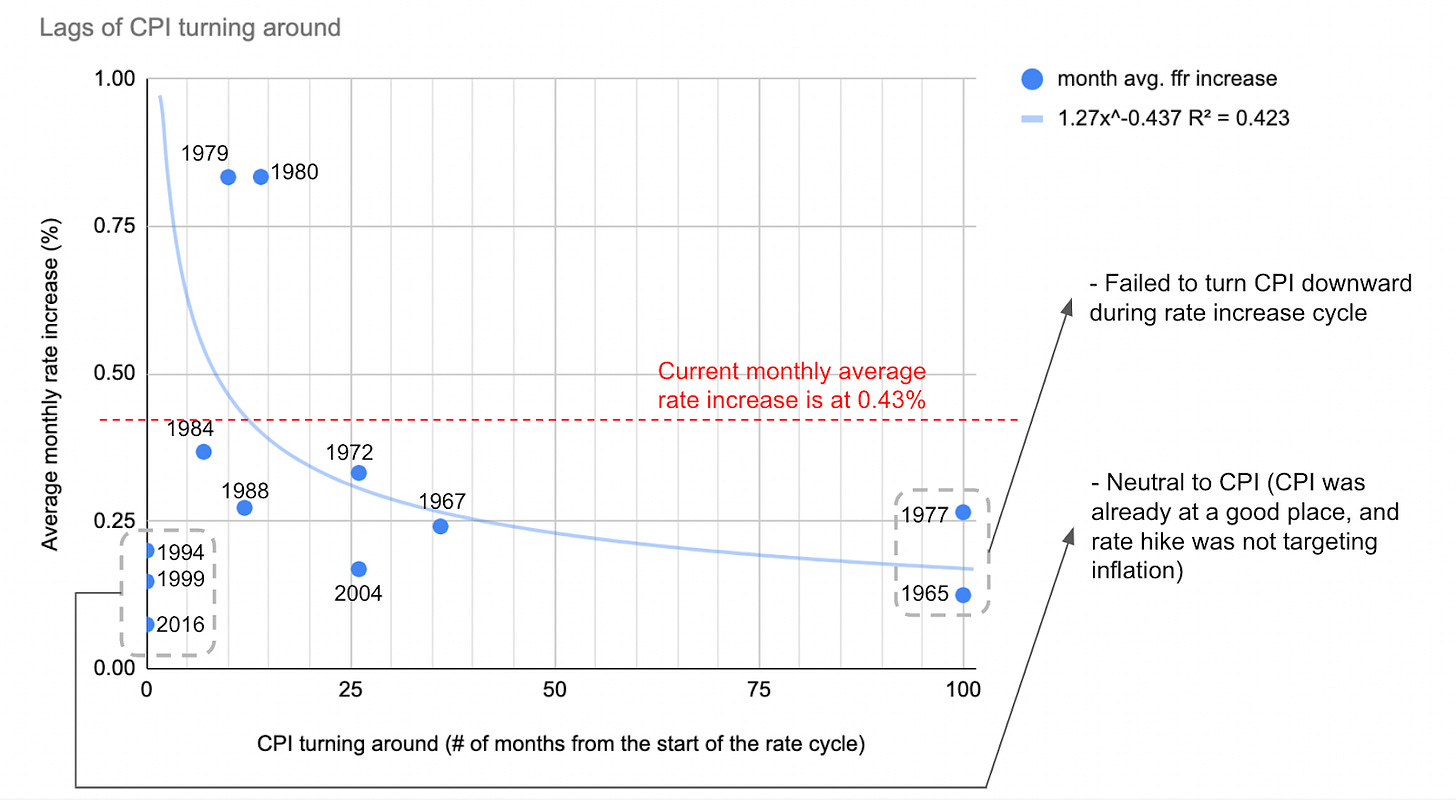

The shortest CPI turnaround is seven months from the start of the first rate hike (in 1984). The most prolonged successful turnaround was 26 months in 1967. On average, CPI took 19 months to come down after the initial rate hike (for successful rate hikes).

FOMC meets eight times a year. The Fed is committed to a 75 basis point raise every meeting. Without an emergency rate hike, we can expect the 75 basis points to continue. This averages to a 50 basis point monthly increase.

Rate increases below 50 basis points per month had a 28% failure rate. The two rate hikes of 82 basis points per month succeeded with an average lag time of 12 months. We expect the current rate hike to require more than 12 months of lag time to bring down CPI since the rate hikes are smaller than 82 basis points.

What’s needed to bring down inflation

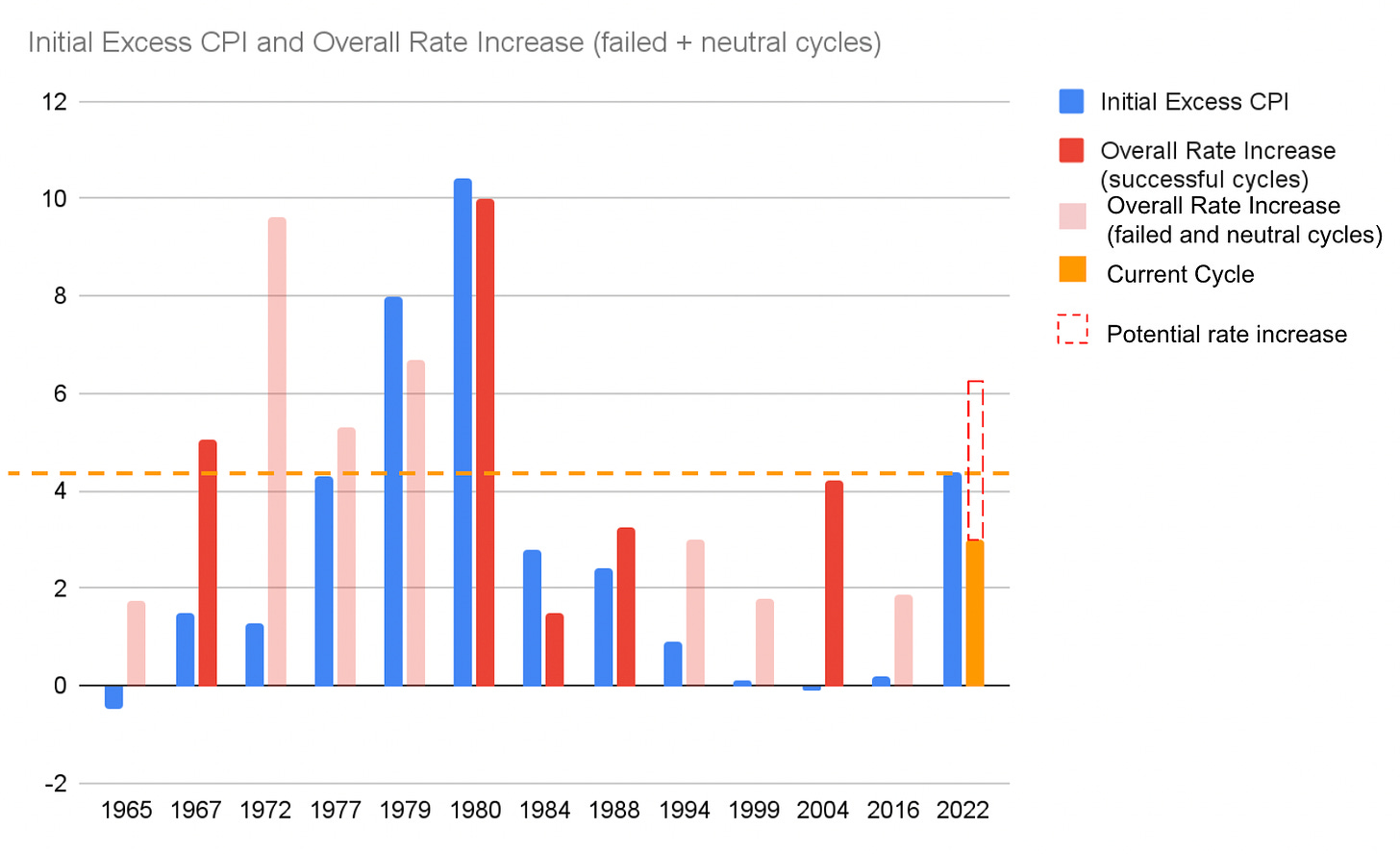

The higher the initial CPI is at the beginning of the rate hike, the more significant the rate increase must be to combat inflation. On average, for the inflation control to be successful, the rate increase to the initial excess CPI multiple is 1.4. Since The Excess CPI was at 4.4% when Fed started the rate increase, if applying the 1.4 multiple, the terminal rate needs to be at least 6.5%. Initial Excess CPI is the initial CPI at the start of the rate increase minus the target CPI of 2%.

A high terminal FFR to CPI ratio (~1.6) is needed for inflation to come down. The Fed projects a terminal rate of 5% to bring down inflation.

Core CPI is at 6.6%. The terminal rate needs to be 9-12% to reach a high terminal FFR to CPI ratio. Unless the Fed doubles the terminal rate target, inflation will be endemic. A repeat of the 70s is likely. Despite the high rate of increase (50 basis points per month), the terminal FFR of 5% is insufficient to bring down inflation to target (2-3%) levels.

This disconnect poses significant risks. Should the Fed increase its terminal rate dramatically, markets will crash hard. If the current terminal FFR is maintained, inflation will become endemic. At this point, the Fed has no good choices. We expect markets to become very disorderly as the markets come to the same realization (inflation is here to stay or the terminal rate doubles).

High Risk Ahead

The Fed projected a confident image, willing to do what it takes to fight inflation. Recent rate hikes of 75 basis points are sufficiently aggressive given the near 0 rates experienced by the markets in the last few years. However, the terminal rate is off by a multiple. The Fed is in a tough spot. Doubling the target rate hike would wreak havoc on the already battered markets. On the other hand, not doubling the target causes endemic inflation and might require a decade to resolve.

The most likely scenario is for the Fed to slowly raise the terminal rate and hike rates simultaneously, pausing in Q2 of 2023 to stabilize the economy before beginning hikes again in Q4 of 2023 or Q1 or 2024. This scenario reduces the possibility that sudden shocks will cause markets to tumble. But this also means markets are unlikely to recover as the Fed moves the goalpost and applies continuous downward pressure.

Seen in context, the current rate hikes have a long way to go, both in terms of time and terminal rate, before inflation turns around. There is no possibility of a V-shaped recovery. Instead, a long and drawn-out high interest and high inflation environment will prevail for the next 5-10 years. Five years is the best-case scenario where the Fed continues to raise rates to 9-12% and maintains the rate until CPI comes down. Ten years is the worst-case scenario where the Fed wavers and does not raise the terminal rate high enough, allowing inflation to become endemic.

Side note: Equity Market Bottom

S&P, on average, bottoms at 70% into the rate hike cycle. To successfully control inflation in one go, this round of rate hikes will likely continue until the end of 2023. Based on this estimate, S&P will likely hit the bottom 15 months into the rate hike, which puts it at mid-2023. Given that the Fed will be the primary force driving the macro landscape in the next 5-10 years, the equity market will respond closely to the policy change. If, as our data suggests, the Fed’s projected terminal rate is only half of what’s needed to fight inflation, we will see significant whiplash in the equity market (and other markets). As cognitive dissonance meets reality, information chaos will cause high volatility as the market tries to find the true bottom.